Marine Air Conditioner Installation

Beat the Heat: A Comprehensive Guide to Installing Marine Air Conditioning

There are few things less enjoyable than being trapped in a sweltering, humid cabin after a perfect day on the water. The air gets thick, cushions feel damp, and sleeping becomes a sticky, restless affair. This is where a marine air conditioning system transforms from a luxury into a near necessity. It’s not just about comfort; it’s about protecting your boat’s interior from mildew and making your time aboard truly relaxing. But installing one isn’t as simple as plugging in a window unit from a hardware store. Marine AC installation is a serious project that demands careful planning and a deep respect for the unique challenges of the marine environment.

As a marine professional who has seen countless installations—both good and bad—I’ve created this guide to walk you through the entire process. We’ll cover everything from choosing the right system to the critical details that separate a reliable, efficient installation from a future headache.

Why You Can’t Just Use a Household AC Unit

Before we dive in, let’s clear up a common question: “Can I just install a cheap portable or window AC unit on my boat?” The answer is an emphatic no. A boat is a harsh environment, and marine-grade equipment is built to survive it. Here’s why a standard unit will fail:

- Corrosion: The salty, humid air will rapidly corrode the coils and electronics of a residential unit. Marine systems use specialized materials like cupronickel for condenser coils and stainless steel components to resist saltwater corrosion.

- Cooling Method: Marine ACs don’t use a fan to cool the condenser like a home unit. They use a continuous flow of raw seawater, which is a far more efficient method of heat exchange. This requires a thru-hull, pump, and plumbing that household units lack.

- Condensate Management: Boats move, heel, and rock. Marine AC units are designed with deep, robust condensate pans and drains to manage the water they pull from the air, preventing spills that can lead to bilge water, mold, and rot.

- Durability: Everything on a boat gets shaken and slammed around. Marine systems are built to withstand the constant vibration and shock of life at sea.

Choosing Your Weapon: Types of Marine AC Systems

The right system for your vessel depends on its size, layout, and your budget. The three main types are self-contained, split-gas, and chilled water systems.

Self-Contained Units

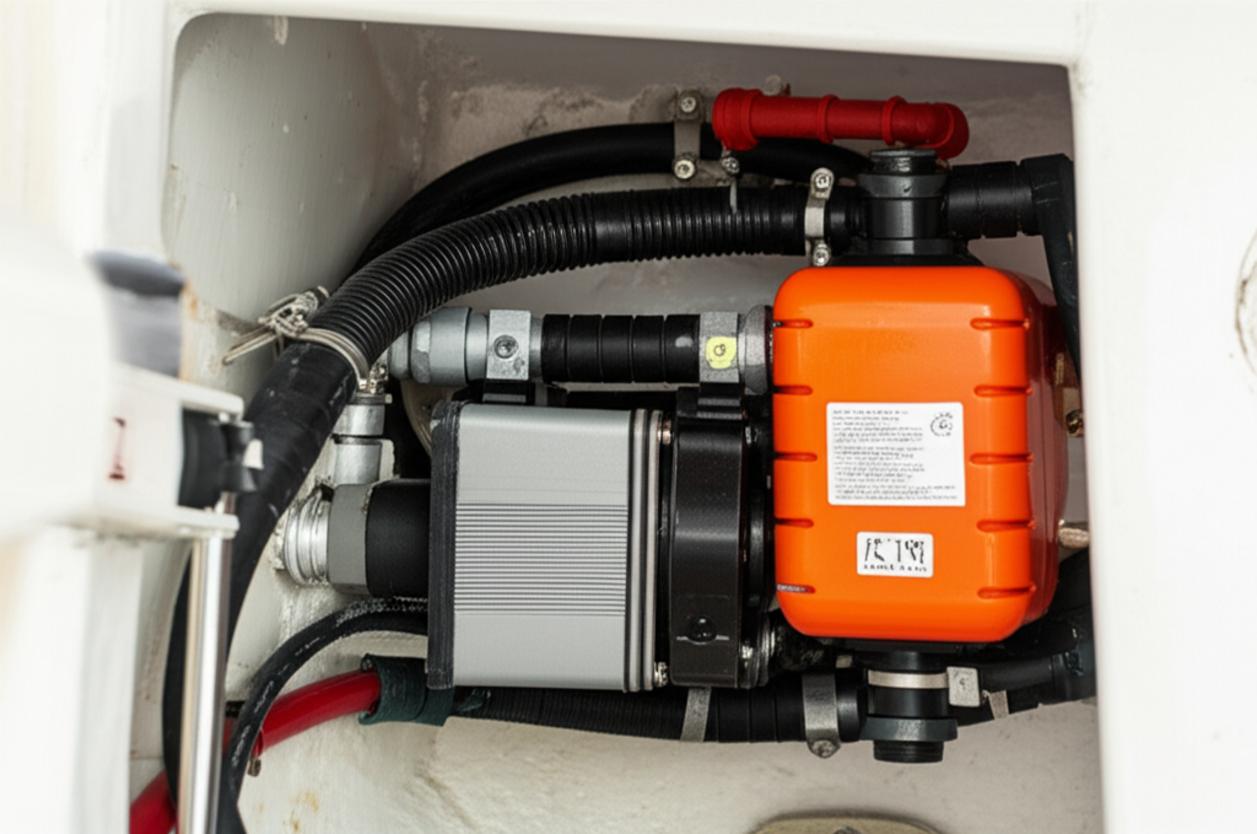

This is the most common type for boats under 40-45 feet. The entire system—compressor, condenser, and evaporator—is housed in a single chassis. You install the unit in the living space (often under a settee or in a locker) and run ductwork to one or more vents.

- Pros: Relatively simple to install, cost-effective, and compact. They are the go-to choice for most DIY installations.

- Cons: The compressor is in your living space, so they can be noisier than other options. They are also less efficient for cooling multiple, separate cabins.

Split-Gas Systems

Similar to central air in a home, these systems separate the components. The noisy condenser/compressor unit is installed in a mechanical space like the engine room, while one or more quiet air handlers are placed in the cabins. Refrigerant lines connect the two parts.

- Pros: Much quieter in-cabin operation and offer great flexibility for cooling multiple areas.

- Cons: Installation is significantly more complex and expensive. It requires handling refrigerant, which legally requires an EPA-certified technician in many places. This is rarely a DIY job.

Chilled Water Systems

Found on larger yachts and commercial vessels, these are the pinnacle of marine climate control. A large chiller in the engine room cools a closed loop of fresh water (mixed with glycol), which is then pumped throughout the vessel to individual air handlers in each cabin. These systems can also provide reverse-cycle heating very efficiently.

- Pros: Extremely efficient, quiet, and scalable for any size vessel.

- Cons: By far the most complex and expensive to install and maintain. Strictly a job for specialized professionals.

The Installation Blueprint: Planning is Everything

A successful installation is 90% planning. Rushing this stage is a recipe for disaster. Here’s your pre-installation checklist.

1. Sizing the Unit: The BTU Game

Choosing the right capacity, measured in BTUs (British Thermal Units), is critical. Too small, and it will run constantly without cooling the boat. Too large, and it will short-cycle, failing to dehumidify the air properly and causing premature wear. A rough rule of thumb is 14-16 BTUs per cubic foot of cabin space. However, you must adjust for:

- Windows and Hatches: Large, unshaded windows add a significant heat load.

- Sun Exposure: A boat with a dark hull or deck will get much hotter.

- Location: A boat in the tropics needs more cooling power than one in New England.

- Insulation: Well-insulated hulls require less BTU capacity.

Consult the manufacturer’s guidelines carefully. When in doubt, it’s better to be slightly undersized than oversized.

2. Location, Location, Location

Where you place the components is just as important as the unit itself.

- The Main Unit (Self-Contained): Find a spot that is low in the boat, central to the area you want to cool, and has space for ducting. Under a berth or settee is common. Crucially, ensure you have easy access for maintenance and a clear path for the condensate drain.

- Return Air: The unit needs to draw in warm cabin air. This return vent should be as large as possible and unobstructed. Never install the unit in an engine room where it could pull in fumes.

- Supply Vents: Position your cool air supply vents high in the cabin, as cool air sinks. Aim for a circular airflow pattern, with the supply and return vents at opposite ends of the space.

3. The Seawater Circuit: The Heart of the System

This is the most critical part of the installation. A failure here can sink your boat.

- Thru-Hull & Seacock: The water intake must be a dedicated thru-hull fitting with a proper marine seacock. It should be located where it will remain submerged even when the boat is heeling or planning.

- Sea Strainer: A sea strainer is non-negotiable. It must be installed between the seacock and the pump to protect the pump and condenser coils from debris. Mount it above the waterline for easy cleaning.

- Pump: The circulation pump must be mounted below the waterline to ensure it stays primed.

- Hoses & Clamps: Use high-quality reinforced marine hose and double-clamp all connections below the waterline with marine-grade stainless steel clamps. Create a vented loop in the discharge line if the outlet is near the waterline to prevent siphoning.

4. Electrical Power: Don’t Skimp on Amps

Marine air conditioners are power-hungry, especially on startup. You need a robust AC electrical system.

- Power Source: You’ll need sufficient shore power (typically a 30A service) or a properly sized generator to run the AC away from the dock.

- Wiring: The unit must be on its own dedicated circuit with the correct size breaker. Use marine-grade tinned wire and follow all ABYC standards for wiring practices.

The Big Question: DIY or Hire a Pro?

Installing a self-contained marine AC system can be a rewarding project for a skilled and confident boat owner. If you are comfortable with fiberglass work (for the thru-hull), 120V AC electrical systems, and plumbing, you can likely tackle the job.

However, you should hire a certified marine technician if:

- You have any doubts about cutting a hole in your hull.

- You are not 100% confident in your AC electrical skills.

- You’re installing a split-gas or chilled water system.

- You want the peace of mind and warranty that comes with a professional installation.

Conclusion: A Worthwhile Investment in Comfort

Installing a marine air conditioning system is a significant upgrade that will fundamentally change how you use and enjoy your boat. It extends your boating season, preserves your interior, and provides an incredible quality-of-life improvement. While the installation process is involved and requires meticulous attention to detail, the reward is a cool, dry, and comfortable sanctuary on the water. Plan carefully, respect the systems you’re working with, and don’t hesitate to call in a professional if you’re out of your depth. Your future, well-rested self will thank you for it.